The myth of the panicky individual investor

How to create a false stereotype through sample bias.

How to create a false stereotype through sample bias.

Sutemi-waza are a class of throws in jujitsu or aikido known as sacrifice throws. They are tricky, but very powerful: they work because of the opponent’s momentum.

There’s a game potential clients and advisors play, and I think everyone loses.

There’s a seduction in behavioral science: 'here’s a bias, go be better by not being biased'.

Sometimes, appearing to be a good advisor works in direct opposition to actually being an effective advisor.

Yesterday I had the honor of opening up the Boulder conference on Consumer Financial Decision Making. Here is my presentation:

“I try pick the managers who will be lucky in the future”

An investor without a faith is doomed.

If money can’t buy what you need, you’re on even footing with the poorest person out there.

🎶 Feel good, make you feel good, I'm looking for emotion, so I know just want to show you baby 🎶

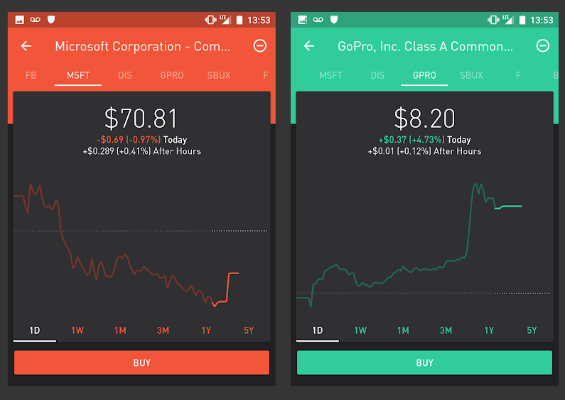

How brokerage app designs show they don't care about success, only activity.

Using technology to be virtuous, effortlessly.

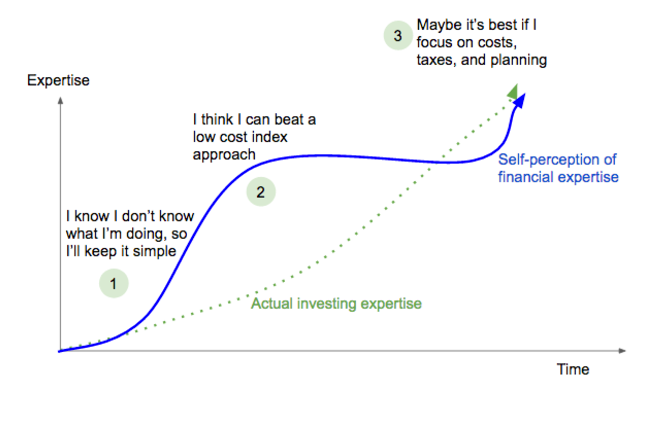

In most areas of life putting in more effort means achieving a better outcome. The harder and more consistently you exercise, the fitter you get. The more hours you put in studying, the better your grades. Of course there are a few, very unusual areas where the opposite rule holds. Aldous Huxley’s called this “The Law of Reversed Effort”: the harder you try, the worse you do. Think of quicksand and finger-cuffs, where success is defined by gentle, slow movements.

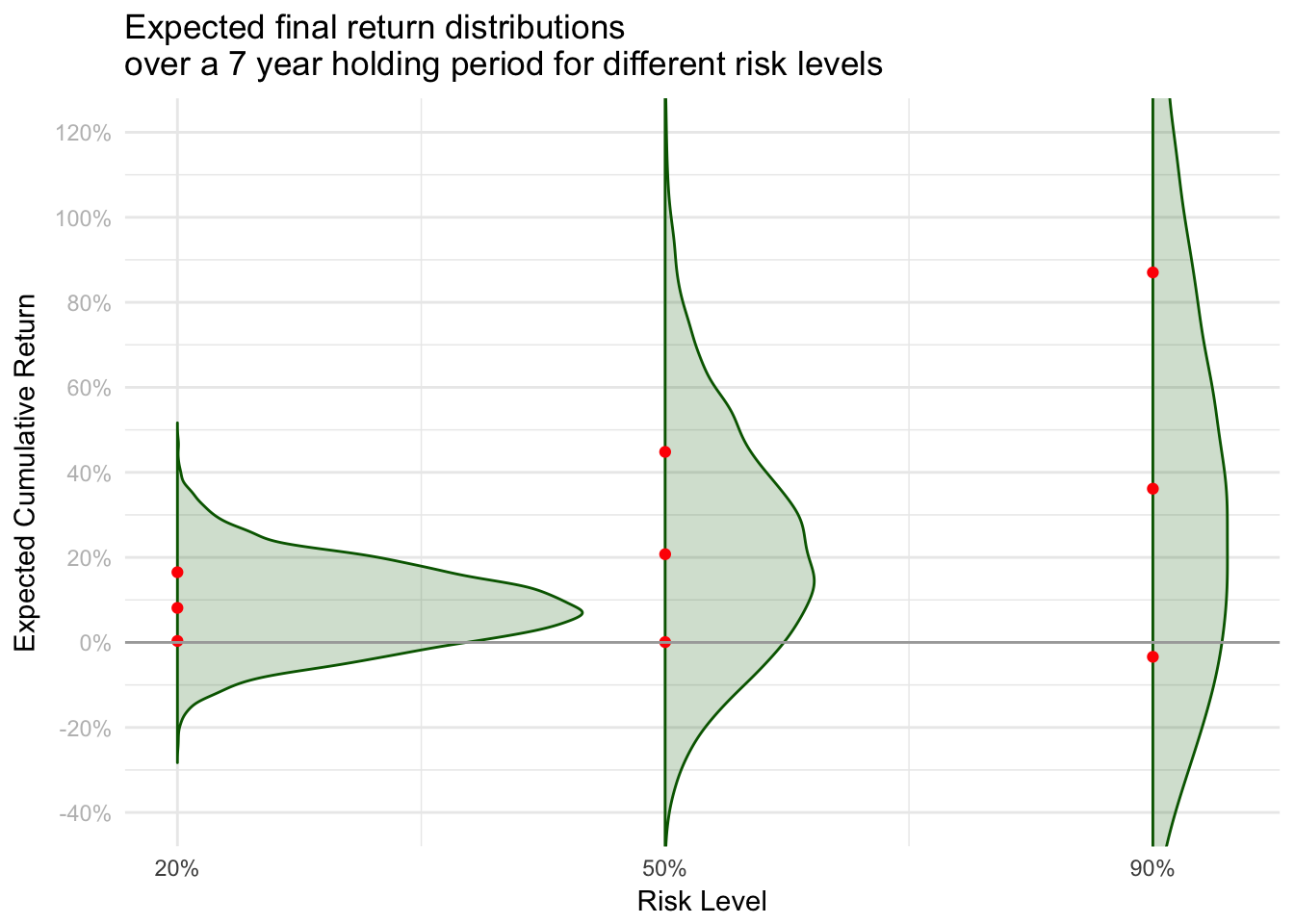

Investors usually understand returns. But risk… risk is more difficult. Risk involves communicating not just that many outcomes are possible, but how likely they are. So I’m in favor of anything that gives investors a better intuition of what risk really is. Andy Rachleff’s post on how the standard efficient frontier graph often misleads investors resonated with me. Investors do often have the perception that the highest return portfolio is best, ignoring the risk.

Do you believe that behavioral biases exhibited by investors can be explicitly addressed through portfolio design?

A curated reading list by what you're looking to get out of it.

Would we recognize intelligence as such if a completely unintuitive architecture or process is performing it?

We all have to climb Mount Stupid.

Planning for individual goals can be very powerful in setting you up for success, but it's good to ocassionally step back and check if the big picture still makes sense.

I believe, and would like to convince more people, that it’s more profitable to help people make better decisions, than to take advantage of how they mis-make decisions.

Some ideas about how to land a niche dream-job.

If you knew you could be happier and make better decisions by blinding yourself, would you do it? Ok, not complete blindness, but just to those factors you decided in advance were irrelevant.

And prohibiting bad behavior just drives it underground.

The future will be stranger than I expect it to be. So how can I experience possible versions of the future before they happen?

I beat the benchmark massively last week. I’ve started swimming again, which has meant regaining ground previously owned. This past week I set recent records in both (speed and distance), which was a huge improvement for me. By Christoffer Engström Let’s be clear: there is no chance I could beat Michael Phelps even if he had one arm tied behind his back. There are people in my pool who are faster than me.

Progressive taxes have some really nice second-order effects.

When a statement makes us feel good, we’re far less critical of it. We want it to be true, and we pay attention to evidence that confirms it, and discount evidence that rejects it.

Yeah, kind of.

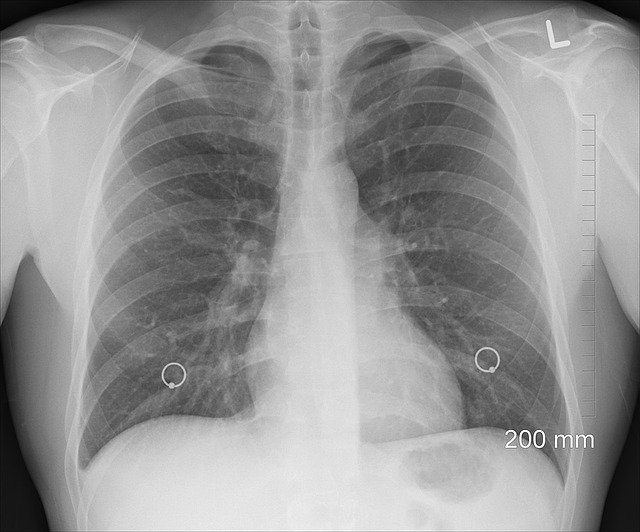

A new paper gives strong indication that on average, individual investors are really poor investors. I mean, really bad.

One of the most provocative questions is what causes some people to end up with lots of money, and some with very little.

Regrets are all about high expectations.

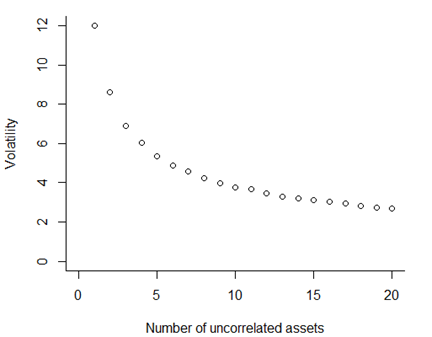

Diversification is always good. It’s just limited in how much good it can do.

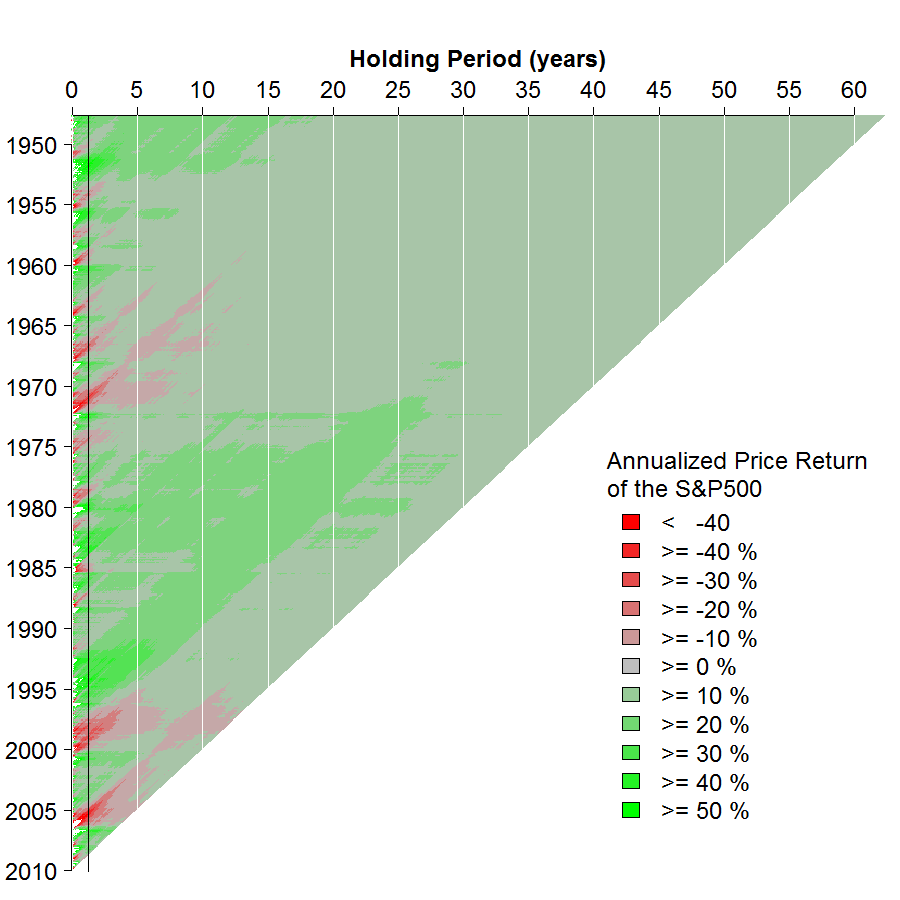

A while ago the great graphics gurus (sorry) at the NYTimes created a very cool graphic showing the annualized returns of the S&P500 over a long time period: This was one of the best graphics I’d seen in a while, but there are a number of things I thought could be improved, or used to illustrate another point. Red doesn’t mean loss. The light red in the picture means a return slightly above inflation.

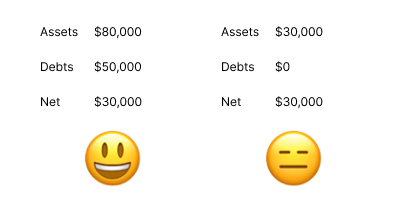

I had the pleasure of meeting up with Abby Sussman of Princeton last night, who investigates the psychology of wealth - assets and liabilities. Her recent piece in Psychological Science sums it up well: We studied the perception of wealth as a function of varying levels of assets and debt. We found that with total gross wealth held constant, people with positive net worth feel and are seen as wealthier when they have lower debt (despite having fewer assets).

I believe unexpected utility is one of the most under-researched ideas in behavioral finance and economics. I, for one, experience it occasionally, and it is the best kind of utility. Photo by Richard Horvath. What, exactly is “unexpected utility”? It’s an experience, usually and hopefully positive, that you completely didn’t remotely see coming. The expectation is key here. Daniel Kahneman, in his recent book, uses the example that the same meal, when made by someone else, often tastes better.

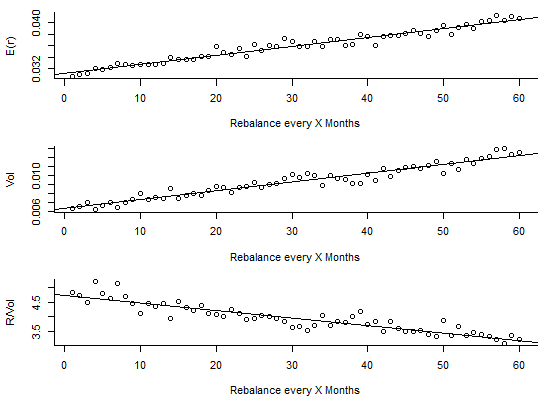

Once we have picked an asset allocation model, how often, or why should we rebalance? I’ve seen multiple conflicting findings about the usefulness of rebalancing. Many such conflicts happen in time-series data because the sample you use can influence things quite strongly. I therefore wanted to see if there was a simple, purely statistical basis for rebalancing. To do this, I simulated some pretty vanilla portfolios with the desired characteristics. Note that as this isn’t real data, it doesn’t have some of the finer characteristics of true returns data such as auto-correlation of volatility.

A problem I occasionally encounter when trying to improve behaviour in the real world is the fairness of control groups. Imagine you have a potential cure for a problem, but you have no proof that it actually works. A standard experiment would randomly allocate individuals to treatment and control conditions, run the experiment for a set period of time, and compare outcome variables. You’d then know if there was a strong effect.

An article in the most recent JDM makes two valuable points – sometimes winning is losing, and we’re ok with that. Some individuals are more likely to over-bid, purchasing a lottery for more than it’s best possible value. Why might they do this? Because to some people, very competitive people, it seems that “winning” is as (more?) important than making a genuine profit. This effect is probably reinforced in circumstances that meet the Winners Curse, in which optimism about ones incomplete information is compounded by a desire to “win”.

I’ve wondered about the following question a number of times: How might the fact that we operate in base-10 (0,10,20…100…200) influence our decisions? We all know that we occasionally make decisions based on simply rounding up or down. But do round numbers influence trading in the stock market - for example, when setting stop or limit orders? Consult a new paper in Management Science: This paper provides evidence that stock traders focus on round numbers as cognitive reference points for value.

The vast majority of research on individual investors’ performance gives a depressing view. The conclusion is usually that individual investors hurt themselves by their trading, and would achieve higher returns adopting a more passive buy and hold strategy. This implication is often incorrect, and many of the studies need to read critically to understand exactly what they are saying. I think there are three implied questions which are answered by these studies:

Historically, I think Americans have been pretty happy with procedural fairness. If we know the rules are applied fairly, we can accept unfair-seeming outcomes. And this is most relevant when seemingly unfair outcomes happen, when some people take home a much larger slice of the pie. However, what if we don’t know how “fair” the rules are? How am I supposed to know if the modern economic system is fair, in terms of procedure?

Do wages in the banking sector reflect “conspicuous consumption?” Yes, bankers like showing off their wealth. But perhaps that’s not the problem. I see the opposite end of this in my volunteering. I help out at an employment center, and was helping a woman write up her resume. She had cleaned and done inventory for a living, and was still searching for a job in similar low-wage occupations at the age of 50.

My senior thesis was on the potential effects of wind energy on electricity markets, so I was very happy to see questions (HT MR) about the short-term/long-term dynamics of electricity markets. I want to focus on exactly the same issue, but as regarding wind-power. Photo by Thomas Reaubourg For a quick background, electricity markets are one of the more unusual, in that generation capacity takes a long time and a lot of money to increase (in the form of generation plants), and the larger the up-front capital costs of the plant, the lower the per-unit marginal costs of generating electricity.

Over at the NYTimes Bucks Blog, people are angry that a bank might actually charge you for the services they supply. This reminds me of people who think they shouldn’t have to pay for investment advice either. Why would someone invest their time, resources and set up the required infrastructure for [running a bank account / giving investment advice] unless they thought they would make a living doing it? They need to get paid somehow too, and the question is, how?

Holidays and vacations are wonderful. They give use a break from the stress and monotony of the workplace, a time to catch up with friends and family, and a chance to see new and exciting places. And part of the enjoyment of a holiday is looking forward to it. Knowing that you have something good coming up lets you enjoy that experience before you even have it, and can change your well-being long before you actual experience it.

Last week saw a couple in Scotland win the £161 million Euro-millions lottery, a truly enormous amount for any individual to suddenly have in the bank. Research indicates that they need to approach their new-found wealth as a source of potential danger as well as happiness. What do we know about the effect of winning the lottery (or unexpectedly inheriting a significant sum)? Obviously, they are now freed from the worries and stresses that come with not having enough money.

From the department of “No, really?”, a new paper showing that we are happier on weekends: This paper exploits the richness and large sample size of the Gallup/Healthways US daily poll to illustrate significant differences in the dynamics of two key measures of subjective well-being: emotions and life evaluations. We find that there is no day-of-week effect for life evaluations, represented here by the Cantril Ladder, but significantly more happiness, enjoyment, and laughter, and significantly less worry, sadness, and anger on weekends (including public holidays) than on weekdays.

“Alpha”, most commonly known as beating the market on a risk-adjusted basis, in laymans terms means doing better than a passive strategy, better than most other dollars or pounds in the market. While obviously alpha is a good thing, there is no guarantee of achieving it – it is a risky prospect itself, but the fees associated with active management are a sure thing. So taking on manager risk as well as market risk implies that there is significant value to active management.

The Economist on using “nudges” and other behavioral economics tricks for improving pension and retirement savings: ALBERT EINSTEIN IS said to have described compound interest as the eighth wonder of the world. It should also be a boon for workers planning their retirement. Start saving early enough and a pension becomes much more affordable. Unfortunately young people are often unable or unwilling to take advantage of this miracle. Their wages are low and their main priority may be to pay off their student debts or to save for a deposit on a house.

Dan Goldstein notes the intuitiveness of using graphical representations of probability, especially in Bayesian settings. High-quality , sometimes even interactive, graphics and charts, have increased greatly in recent years as news and other information have migrated to the web. The New York Times has a dedicated staff of graphical artists well versed in information design, and many digital graphical artists are becoming better versed in statistics and displaying ideas and results.